Elizabeth DESSIE, Mauritania, mai 2013

The sustainable livelihoods approach as a transformation tool for the Western Sahara conflict

This paper presents a new take on the transformation of this frozen conflict, suggesting ideas on how a case-specific implementation of the livelihoods approach can act as a viable strategy for solving a forgotten refugee crisis.

Introduction

As one of the world’s longest running disputes, the Western Sahara conflict finds itself outside the loop of mainstream politics on the international arena. The Sahrawi people, most of which have found refuge in neighbouring Algeria, face an alarming livelihood crisis which, unless adequately addressed, may have far-reaching impacts on political, human and regional security. Despite living in exile for years, the Sahrawi refugees’ lives are confined to the boundaries of the camps, where prospects for self-reliance and sustainable livelihoods are inevitably constrained and limited. Drawing from the theoretical foundations underpinning Robert Chambers’ sustainable livelihoods framework, this paper presents a new take on the transformation of this frozen conflict, suggesting ideas on how a case-specific implementation of the livelihoods approach can act as a viable strategy for solving a forgotten refugee crisis.

1. The Western Sahara conflict

Often referred to as the last colony of Africa (Smith 2009, p.6), the political status of Western Sahara has been complicated, to say the least, since its decolonisation in 1975 and remains uncertain to this day. Following Spain’s hasty exit from its former colony, Morocco and Mauritania jointly invaded the territory, setting off a sixteen-year long dispute and the large-scale displacement of the Saharawi population. (Wilson 2011, p.11). With Mauritania withdrawing in 1979, Morocco proceeded with further extensive occupation has remained there since. Thus partially annexed, the territory is still on the UN list of non-self-governing territories under the name of Western Sahara (UN General Assembly 2009).

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), founded in 1976 by the Western Sahara’s liberation movement, the Polisario Front, created a governmental structure based in refugee camps in Algeria, located near the Algerian town and military base of Tindouf. Whereas Mauritania signed a peace agreement with Polisario in 1979 and granted recognition to the newly formed SADR, the war with Morocco only came to a halt in 1991 with the declaration of a ceasefire and the deployment of a UN peacekeeping force, UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) in the territory. This referendum, proposed as a means of enacting the right to self-determination of the Sahrawi people, is yet to take place (Wilson 2011, p.14).

Today, Western Sahara is divided politically, militarily, and geographically by a 2,200km-long Moroccan-built defensive berm. About a fifth of the territory, lying east of the berm, is controlled by the Polisario Front (Smith, D.V. p. 3). A territory known to be rich in fishing waters, mineral resources, and extensive phosphate deposits, Western Sahara is believed to harbour substantial iron ore and large offshore oil reserves (Zoubir 2010, p. 76). Although Morocco has persisted with its economic plans in the territory, the disputed status of Western Sahara and its existence under international law denounced the external use and disposal of its natural resources (Wilson 2011, p. 18).

The exiled population stands in contrast to the annexed population which lives in the areas of Western Sahara under Moroccan control. Due to the limited data and resources on Saharawis living in the annexed parts of Western Sahara, obtaining accurate or reliable information about the situation in the territory is hampered by highly restricted access to the occupied zone. Although Morocco has allowed a limited number of journalists, NGOs, and independent observers to enter the region since 1998, their movement is curtailed and closely monitored (Smith D.V. p. 7). As a result of this absence of transparency, it was not possible to assemble sufficient amounts of data related to displaced Sahrawis still residing in Western Sahara, therefore this paper will only focus on the experiences of the exiled population in neighbouring Algeria.

Exact figures for the size of the refugee population are difficult to obtain; however the most consistent figure quoted by the UNHCR suggests there are 165,000 Sahrawi refugees hosted in Tindouf (UNHCR 2013). This population is heavily dependent on aid spanning from food, and water to health services. Although international aid agencies and the Polisario Front have created a relatively efficient system of assistance delivery throughout the camps, the reality of the crisis proves the refugees have existed in isolation for almost 40 years and still lack a just and viable solution to their unclear state of existence (Wilson 2011, p. 4).

2. The Sustainable Livelihoods framework

As defined by Robert Chambers and Gordon Conway in 1992, a ‘livelihood’ “comprises the capabilities, assets and activities required for a means of living: a livelihood which is sustainable can cope with and recover from stress and shocks, maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation; and which contributes net benefits to other livelihoods at the local and global levels and in the short and long term (SIDA 2001, p. 16). Further developed by the British Department for International Development (DFID), the concept was integrated into the agency’s programs for development cooperation, starting from the mid ‘90s. Chambers’ idea of ‘sustainable livelihoods’ (SL) constitutes the basis of the sustainable livelihoods approach (SLA) and the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF).

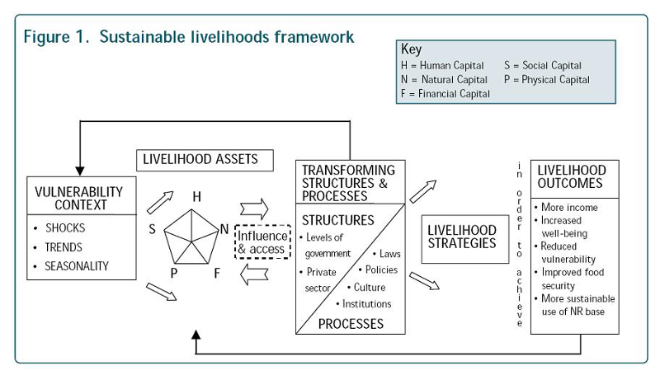

While the definition of a livelihood can be applied to different hierarchical levels, it is used most commonly at the household level. The SLF commonly serves as an instrument for the investigation of poor people’s livelihoods, whilst simultaneously visualising the main factors of influence (Hussein 2002, p.8). As shown in Figure 1, livelihood strategies comprise of a combination of activities and choices that people make in order to achieve their livelihood goals. As they are never static, they have to be understood as a dynamic process of constantly changing relationships between the elements within the framework and with external forces as well (ISDR 2010, p. 34).

Of the various components of a livelihood, the most complex is the portfolio of assets out of which people construct their living, which includes both tangible assets and resources, and intangible assets such as claims and access. Like all models, the SLF does not represent the full diversity and richness of livelihoods, which can only be understood by qualitative and participatory analysis at the local level (SIDA 2001, p. 25). By drawing attention to the multiplicity of assets that people make use of when constructing their livelihoods, the SL Approach produces a more holistic view on what resources, or combination of resources, are important to the poor, including not only physical and natural resources, but also their social and human capital. In this way, the SLA has to be understood as a tool aiming to understand poverty in responding to poor people’s views and their own understanding of their situation. Its application is therefore flexibly adaptable to specific local settings and to objectives defined in a participatory manner (Development Study Group 2002, p. 14).

3. Implementing the approach

The research on livelihoods and the SLF were not developed with conflicts, displacement and resettlement in mind. Moreso, these concepts evolved as tool to guide research to explore existing and alternative routes to sustainable livelihoods for poor people in contrasting agro-ecological settings (Wilson 2011, p. 22). As yet, there is no such system in place aimed at either exploring the livelihood potentials available to Sahrawi refugees in Algeria, or focused at re-establishing those lost throughout the course of the conflict. Although organisations such as the UNHCR and Oxfam have been working in the camps addressing health, water and food security issues, the reality of the crisis and its duration have made the challenges increasingly complex and difficult to cope with (Smith, D.V. p. 15).

The classification of basic conditions needed for the improvement in sustainable livelihood forms a central part of SL research. The following analysis will discuss the relevance of these conditions within the context of the refugee crisis, the viability of the approach, as such, and outline the ideal prospects of framework designed to revive, reinvent and improve the livelihood opportunities of the displaced Sahrawis in order to achieve a sustainable long-term solution to their ongoing predicament.

4.1. Asset-building

Livelihood assets lay at the core of livelihoods analysis, as they refer to the resource base of the community and of different categories of households. The size and shape of the asset pentagon – that being, the amount and relative importance of each type of capital – varies between communities and between wealthy and poor households within the same social structure (DFID 1999, p. 6). Since the ceasefire in 1991, political and social détente in the Tindouf refugee camps has nurtured growing economic entrepreneurialism, which has contributed to greater freedom of movement in, from and through the camps. Prior to this period, however, there was no circulation of money in the camps as all economic affairs were conducted on an exchange basis. Moreover, dire political developments in Algeria and overshadowing events in the world since 1991 have affected the flow and reliability of vital aid to the refugees (Wilson 2011, p. 13).

The focus on livelihoods, such as the growth of crops, concerns itself with the promotion of economic self-reliance until exile comes to an end. As such, while it is an enormous step forward, it does not go far enough. Fostering the asset-building process would prove a more farsighted policy (Development Study Group 2002, p. 17). To promote asset-building, it is vital that development practitioners see refugee communities as viable economic actors in their own right. With that in mind, a focus on the transferability of these assets would significantly complement current policies in refugee settings (McDougal 2006, p. 24). In other words, sustainable poverty reduction will entail success only if development agents work with affected people and with their current livelihood strategies, social environment and capabilities ready to adapt. At a practical level, this implies a detailed analysis of people’s livelihoods and their dynamics over an extensive period of time. Through the integration of elements constructed within SL research, a new framework that would enables researchers to account for changes to the basic material and social, tangible and intangible assets that people have in their possession, and to track the impact of these changes on their livelihood strategies could have far-reaching impacts (Conway 2004, p. 46).

4.2. Replacing vulnerability with security

The Saharawi refugee camps, mostly made up of women, children, and the elderly, are run by the Polisario Front and the refugees themselves. With little outside interference, they have organised themselves into four large units called wilayas, with each wilaya divided into smaller units, called dairas (Wilson 2011, p. 15). The link between the vulnerability context and asset ownership is key to our analysis. On one side, assets help protect people’s livelihoods against shocks, while on the other hand, shocks cause people to lose their assets. (Smith 2009, p. 24). While the provision of security is about ensuring that refugees have the necessary physical and economic tools to lead productive existences, resilience is the ability to withstand and recover from shocks.

Although methodologically, the livelihood framework demands information gathered through a variety of methods in several areas of focus - including surveys, interviews and participatory methods – SL research is primarily concerned with livelihood strategies as outcomes. Sustainability in the livelihoods discourse does not infer the sustaining of present livelihoods without change; rather, it infers livelihood strategies that lift people out of poverty, enable them to cope with future shocks and stresses, and in a manner that enhances the natural resource base (McDougal 2006, p. 19) Therefore, when blended together, this approach and methodology can shape the analysis and evaluation of data leading to an understanding of livelihood complexity, as in the context of the Sahrawi refugees.

On the other hand, we must bear in mind that this type of advancement would demand a detailed understanding of the linkages between impoverishment, livelihood re-establishment and sustainability under given conditions (EfD 2008, p. 14). Given the appropriate resources and the possibility of a constructive means of implementation, an innovative handling of the SLA with a focus on inclusive growth could, potentially, improve the livelihood opportunities of the Sahrawis and thus transform the crisis into a circumstance.

4.3. Institutional dynamics

As livelihoods are formed within social, economic and political contexts, institutions, processes and policies - such as markets, social norms, and land ownership - affect the ability of vulnerable populations to access and use assets for their benefit. As these contexts change, they create new livelihood obstacles or opportunities, or as in most cases, both simultaneously (Hines and Balletto 2002, p. 11). Local institutions that are undemocratic and unaccountable to local community members have a greatly disabling impact on those in need, as they reduce their chances of getting themselves out of the poverty trap.

The SL approach regards institutional processes as central to livelihoods. In its conceptual framework, DFID includes power relations as one aspect of ‘transforming processes’ to be examined; more so, the way resources and other livelihood opportunities are distributed locally is often influenced by informal structures of social dominance and power within the communities themselves (Brock 2001, p. 9).

Therefore if applied consistently, the SL approach could assist in creating enabling policies and institutional environments which could make it easier for the Sahrawis to gain access to assets – such as land and livestock – in order to secure new livelihoods. The risk, however, lies in the possible ‘outgrowth’ of this process, which may cross beyond the practical realities of local development administrations. Therefore it is key to ensure the particular interpretation of the SLA always reflects the context within which it is supposed to function and to ensure that the livelihoods of the local population remain their greatest recovery priority (Development Study Group 2002, p. 27).

4.4. Identity as a livelihood asset

Since the exodus of the Sahrawi population Algeria, the state-in-exile has proceeded with the implementation of a National Action Program directed at transforming the refugees into citizens capable of leading their own future nation-state upon their return to their homeland. As a result of these efforts, much emphasis has been placed on developing human capital and striving for self-reliance (Smith 2009, p.6). As mentioned earlier, the current size of the Sahrawi population in the refugee camps is believed to be in the region of 165,000. A complex web of interactions between refugee and host populations has developed over the last three decades and the duration of the conflict has resulted in the creation of a new Sahrawi identity (Wilson 2011, p. 21)

According to the UNHCR, the key challenge for international assistance in protracted refugee situations is finding out how to best support host governments in gradually assimilating refugee populations into the labour market and formal economy, as well as providing adequate training and livelihood support to enhance their self-reliance (UNHCR 2006, pp.56-57). The creation of opportunities through an SL analysis would involve promoting activities which would enable individual households to lift themselves out of poverty, and thus elevate at least a fraction of the refugee population into a more progressive and promising degree of autonomy. Furthermore, the role of social diversity - within which gender relations play a key role - forms a central part in outlining the challenges of social inclusion and universal access of rural people to basic health, education and economic infrastructure and services (SIDA 2001, p. 34).

The livelihoods approach may also be used to systematically examine differences in livelihood system of groups that are traditionally disadvantaged and marginalized, as is the case in Tindouf. On the basis of their personal goals, the potential asset base of the Sahrawis and their understanding of the options available would, eventually, develop and pursue different livelihood strategies. Ideally, a thorough implementation of the livelihood framework could transform the uniqueness of their culture and social structures into a strength and thus contribute to creating a durable solution. Moreso, participation in community-level socio-cultural and political activities, which are an impartial element of the livelihood system, must be considered (Brock 2001, p. 12).

4.5. Strategies to create opportunities

As achievements of livelihood strategies, livelihood outcomes might give us an idea of how people are likely to respond to new opportunities and which performance indicators should be used to assess support activity. Livelihood outcomes directly influence the assets and change dynamically their level - the form of the pentagon - offering a new starting point for other strategies and outcomes (Development Study Group 2002, p. 31). Providing livelihoods opportunities for displaced populations is a tool for protection, and should be coordinated with protection actors. Moreover, livelihoods initiatives should aim to protect and promote food security, where feasible, through agricultural production, small businesses and employment.

Legal and policy restrictions in countries of asylum often prevent refugees from accessing formal employment opportunities, credit support, land for agricultural production, and/or restrict their freedom of movement (UNHCR 2006, p. 37). Even if Sahrawi refugees receive permission to leave the camps, it is virtually impossible for them to work legally in Algeria. As mentioned earlier, the Sahrawis have created their own network of informal businesses in the camps and surrounding areas; yet they are not able to find legal jobs in the rest of the country, or own property, for that matter (Smith 2009, p. 9).

To tackle these issues, a focus on adaptive livelihood strategies aimed at balancing livelihood objectives could create beneficial outcomes. These systems could include voluntary movement, the division of households, re-establishing collective labour systems and communal land-holding, maintaining links to established camps and innovative protective strategies (SIDE 2001, p. 43). Furthermore, when taking into account the spatial patterns of available resources and their management related to the Sahrawi crisis, the temporal dynamics of land-use and livelihood systems over time, and the relationship between processes taking place at different scales -from macro to micro - could produce a range of diverse opportunities not just for research purposes, but for implementation and policy design as well (McDougal 2006, p. 31).

4.6. Leads and prospects

The SL approach to understanding livelihood processes suggests a research agenda in the context of sustainability, which takes account of various capitals, including livelihood resources, institutions, strategies and outcomes (Conway 2004, p. 23). The approach can, therefore, enhance research into disaster-related impoverishment risks and livelihood reconstruction in involuntary resettlement situations. Scoones (2009) pointed out that in order to fully grasp the complex and differentiated processes through which livelihoods are constructed, we must analyse the institutional processes and organisational structures that link these various elements together. To do this, it is essential that SL analyses fully involve the local people to let their knowledge, perceptions, and interests be heard (Brock 2001, p. 24).

It must be noted, however, that although the SLA is, by definition, unique to the specific context within which it is applied, it does not represent a magic tool able to eliminate problems of poverty in a blow, nor is it a revolutionary idea that will transform development research and cooperation (Wilson 2011, p. 17). In the context of the Western Sahara conflict, we should take advantage of the flexibility and openness of the SL approach by exploiting the tools it provides and applying them to our study for research and policy purposes. As the concepts are not restricted to livelihood thinking only, we can use the framework and adapt it to our needs, regardless of the issue we encounter within its relevant sphere of functionality.

What this analysis has shown is the central role of the notion of livelihood strategies, equal access to resources as an imperative of a sustainable solution, and the mediating role of institutions. Furthermore, we discovered that policymakers need to regard protracted refugee situations through the lens of economic livelihoods and thereby contribute to creating a mechanism that would allow for asset transferability in enabling refugees to redefine themselves in a time of vulnerability into an economic legacy (McDougal 2006, p. 31) Although the SLF was not designed to specifically address circumstances linked to conflict resolution, transformation or population displacement, the values coded within the livelihood concepts can be applied to situations of forced or involuntary resettlement following disasters or the construction of development projects (Conway 2009, p. 28). Moreover, the approach also facilitates an understanding of the underlying causes of poverty by focusing on the variety of factors, at different levels, that directly or indirectly determine or constrain access to assets of different kinds (Development Study Group 2002, p. 21).

This analytical attempt at implementing the livelihood approach to a conflict case-study proved there is more research to be done on the process of livelihood destruction and its re-establishment among resettled communities displaced as a result of conflict. Following considerable investment into expanding this realm, we can hope the SLA will continue to help shape research to better understand the impacts and help rebuild the livelihoods of affected populations in an innovative and sustainable way.

Conclusion

The Western Sahara conflict is an example of an environmental and human crisis removed from the attention of the international community. The continuing refugee crisis in neighbouring Algeria, which hosts tens of thousands of Sahrawis in camps in the city of Tindouf and surrounding areas, acts as the most alarming impact of the thirty-year long dispute. The poor living conditions and lack of livelihoods has forced the refugee population into a state of dependency on aid, without leading prospects of self-reliance. Since the ceasefire of 1991, political and social détente in the refugee camps has nurtured limited economic entrepreneurialism which, however, does not extend into the rest of Algeria, thus creating a marginalized island of poverty inhabited by a structurally weakened population (Wilson 2011, p. 13).

The sustainable livelihoods framework, grown out of the foundations introduced by Chambers and further developed by DFID, is a tool frequently used by development agencies for planning and assessing development interventions. The SLA can be defined in terms of the ability of a social unit to enhance its assets and capabilities in the face of shocks and stresses over time. Within the definition, livelihoods, as such, contribute to food security, prevent dependency, reduce vulnerability, enhance self-reliance and can develop or help build a set of key skills during displacement, which may have a positive impact on well-being of those affected (Brock 2001, p.18). Following the outcomes of this analysis, we can rightfully call the SLF a “useful tool to structure development research” (Development Study Group 2002, p.11).

As protracted refugees, the Sahrawis are neither natural nor inevitable consequences of involuntary population flows; they are the result of political actions, both in the country of origin and in the country of asylum. Therefore, their situation is an outcome not of vulnerability, but of political inaction. Needless to say, a just, lasting and mutually acceptable political solution based on the principles of international law would, understandably, be the most effective manner of addressing the Sahrawi refugee issue. In the meantime, the proposed interpretation of the sustainable livelihoods approach could, potentially, help us understand what a sustainable livelihood means in the context of an acute refugee crisis dormant to the outside world.

Notes

Paper Presented at the Observatory of Contemporary Mauritania (Observatoire de la Mauritanie contemporaine) 6th May 2013.

Picture of the article « Le conflit du Sahara occidental se radicalise », by Thierry Oberlé, Le Figaro, 2010-11-10.

Fiches associées

Fiche de bibliographie : References: The sustainable livelihoods approach as a transformation tool for the Western Sahara conflict

Elizabeth DESSIE, Mauritania, mai 2013